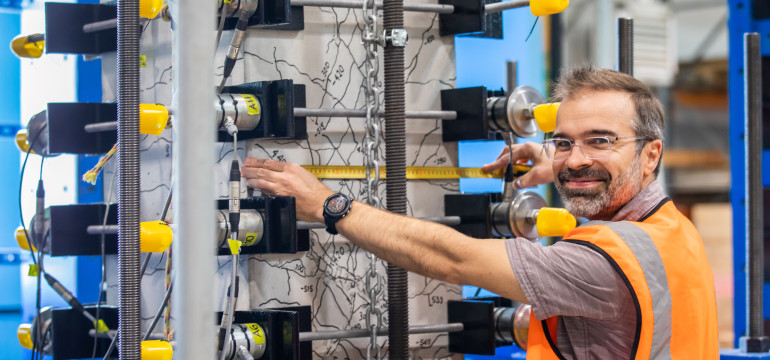

Researcher profile: Professor Santiago Pujol

Professor Santiago Pujol

When thousands of people were killed and injured by a major earthquake in Colombia’s coffee growing region, Santiago Pujol was at the beginning of his career as an earthquake engineer. Even then, he felt responsible for the huge level of damage and devastation, which he saw as unbelievable and completely unacceptable.

Over thirty years later, Santiago Pujol is now a Professor of Civil Engineering at the University of Canterbury and incoming Director of Te Hiranga Rū QuakeCoRE.

Prof Pujol is involved in several projects funded by the Natural Hazards Commission (NHC) Toka Tū Ake into designing and retrofitting buildings so that they have a better chance of withstanding earthquakes – a goal he insists is not only morally right, but also makes sense financially.

We sat down with Prof Pujol to ask him more about his NHC-funded work and what’s behind his life-long commitment to preventing deaths and damage by earthquakes. This interview is part of our Researcher Profile series, which highlights the people behind the science we fund.

Q and A

Tell us about your NHC-funded work and why it’s important for New Zealand?

Santiago Pujol: I’ve been working on two projects funded through NHC. The first one involves writing guidelines to help engineers retrofit reinforced concrete buildings built before wide enforcement of current (or “modern,” if you will) building code regulations. The idea is to standardise and streamline approaches to help ensure an adequate level of safety and facilitate more retrofits across the country.

The second project tested the earthquake safety of a common technique used for connecting reinforced concrete walls to their foundation, called ‘staggered lap splices’. The practise is no longer used in several countries because of safety issues, but it’s still allowed here.

We put the seismic “toughness” of staggered lap splices to the test in simulated earthquake motions, and found that they did not withstand the demands as well as it had been expected. This is significant because most of New Zealand’s buildings are built this way. That’s not to say “the sky is falling,” but it does suggest more research into safety and alternative construction methods would be prudent.

What is your personal experience with natural hazards, and how has it influenced your research?

SP: While I was studying civil engineering in Colombia where I was born, there was a small earthquake that rattled my city and I think that’s why I chose to go into earthquake engineering at first.

A few years later, after I started my master’s, there was a more powerful earthquake that shook Armenia, in Colombia’s coffee growing region, killing and injuring thousands of people. The degree of damage and devastation was unbelievable and completely unacceptable.

I went there with my master’s supervisor to try to understand what had happened and someone in the street saw us in our hardhats. They asked if we were engineers and I said yes. They said, ‘this is your fault’, and I remember thinking, ‘they are right’. I do feel responsible for disasters that keep occurring, even in countries where I haven’t worked, because what we do here in Aotearoa (and in the US, where I worked for 25 years) has an impact in other countries.

The Christchurch earthquakes encouraged me to come to New Zealand, because I saw what happened as an opportunity to build more robust, more resilient buildings.

What are your future research or career ambitions?

SP: There are simple tweaks that we can make to the way we build that will improve things radically. So that’s my career ambition, or hope rather, – to convince my fellow engineers that we can do it, we can build better structures, and we can afford it.

We’ve done research that shows that you don’t need to invest much more to improve safety drastically. On average the cost of the building as a whole would go up 1% to 2%. When you compare that with things like realtor fees or interests, it’s clear that as a society we are okay with these types of expenses. But when it comes to this one investment, investment to prepare for the unpredictable , we’re hesitant.

If we do the math, we conclude that we would end up spending less overall and avoiding suffering. The suffering we saw in Antakya, in Turkey, was heartbreaking. I hope we don’t see this level of suffering to make a change in New Zealand.

When I was growing up, only “flimsy” moment-resisting frame buildings were built in Colombia. The right decision, made by the right person, at the right time, to respond to owners facing too much non-structural damage occurring after rather weak tremors, improved earthquake-engineering practice in the country radically. The decision affected one line in the Colombian building code. Yet, thanks to it, engineers had to introduce abundant shear walls in buildings. You could argue that the walls that they use are too thin but, still, the buildings of this generation are an order of magnitude better than the buildings of my generation, and no one in Colombia seems to complain anymore (as far as I know) about cost increases. Turkey is going through the same transformation right now. I am hopeful other countries will go through similar transitions without waiting for devastating earthquakes.

What is your vision for a resilient New Zealand?

SP: A resilient New Zealand is one in which we have more robust infrastructure – buildings and bridges, industrial facilities.

Of course, infrastructure is not the only problem, but it is often the main cause of mayhem when there is an earthquake. I think we need bigger factors of safety and more robustness, especially for key centres such as Wellington. We cannot depend on every building detail to work, because things are not always built right or don’t always work as expected. And even when we build everything right and things work as expected, very often the earthquake is bigger than anticipated.